Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Christopher A. Hartwell (ZHAW School of Management and Law, Switzerland), and Pierre Siklos (Professor Emeritus at Wilfrid Laurier University; and Balsillie School of International Affairs, Canada).

A paper by the two of us, forthcoming in the International Journal of Central Banking, makes the case that poorly performing central banks – in particular, ones that continually miss their inflationary targets – not only undermine their own credibility, but also undermine a country’s institutional quality. Therefore, when asking: What Damage Can a Poorly Performing Central Bank Do? The answer is: quite a lot, actually. Such a conclusion has far-reaching ramifications for institutional development, leading to less overall economic resilience.

Ever since the policy of central bank autonomy spread around the globe, monetary authorities have played, some would say, an outsized role in determining the path of a country’s economy. Given this importance, we hypothesize that how a central bank performs can have a substantial influence on not only the performance of the economy but the strength of its institutions. For example, short-term declines in central bank credibility, a flow variable, imply a parallel decline in the overall trust placed in central banks, with trust a slower-moving stock-like variable. If this trust begins to ebb away from the central bank, there is the potential to degrade a country’s institutions more broadly. Weaker institutions translate into less institutional resilience in an economy. We think of resilience as the ability of a country to withstand shocks, potentially of both the economic and political variety.

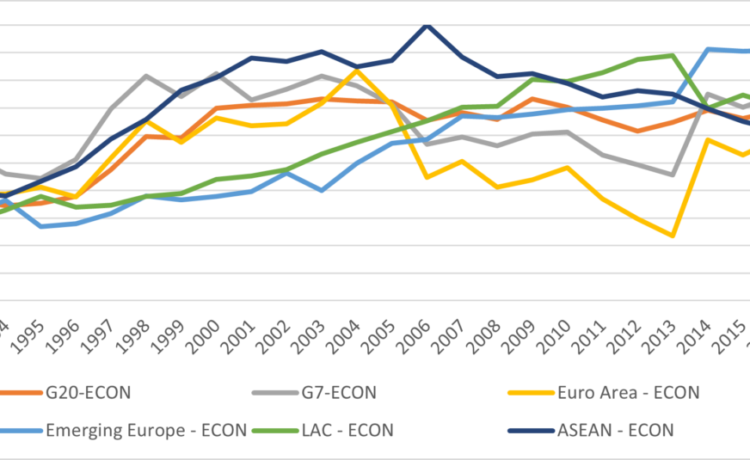

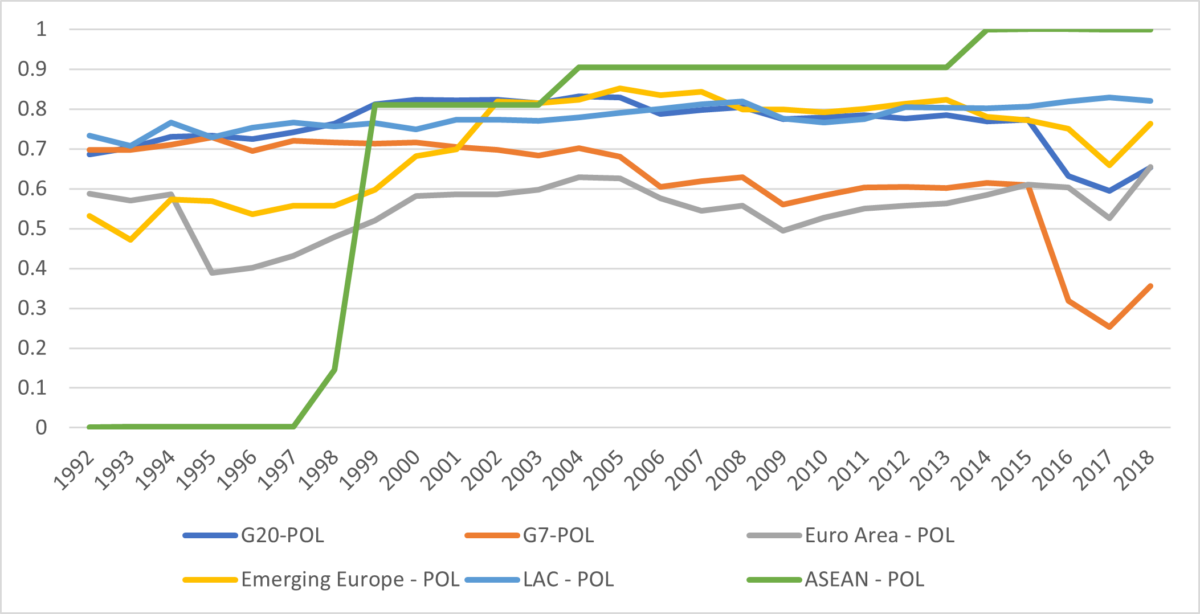

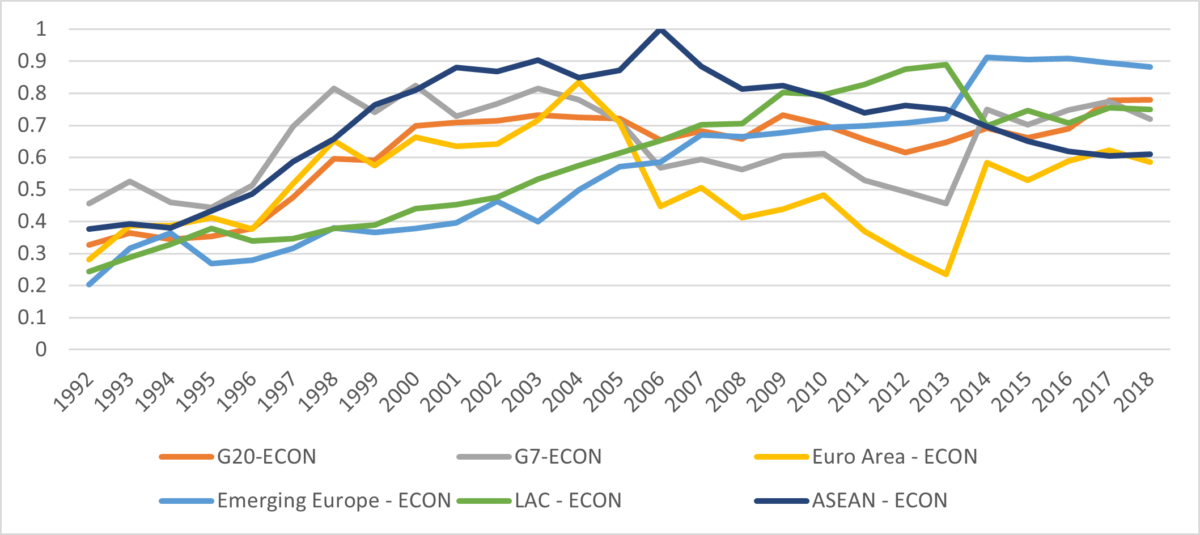

To quantify this relationship, we construct an index of institutional resilience encompassing economic factors (e.g., extent of property rights, extent of openness to trade and finance, and flexibility of exchange rates) and political ones (e.g., democracy, executive constraints, and the fiscal size of government). This index captures attributes that ought to be positively correlated with resilience, apart from size of government, which should be negatively correlated (a large government has little room to maneuver in the face of shocks). The graphs below illustrate our findings for economic and political resilience (the index ranges from 0 to 1) for selected country groups, although we have generated these indices for each of the over 90 individual countries in our data set (representing over 80% of global GDP). While our data go back to the 1960s, it is only by the 1990s that the widest array of variables considered are consistently available for countries beyond the advanced economies. As shown below, the 1990s and 2000s have seen a global rise in central bank resilience although there is considerable variation over time and the gaps between the country groups shown show fewer signs of convergence by the end of the sample that in the early 1990s. Gaps in political resilience remain throughout the sample considered and there is a marked drop for the G7 countries beginning in 2015 that predates the pandemic and recent events. The G7 were among the most politically resilient in the early 1990s.

Figure 1: Economic Resilience. Higher scores imply greater resilience

Figure 2: Political Resilience. Higher scores imply greater resilience

We array this index against a measure of central bank effectiveness, which is linearly comprised of three separate components. First, we compare a central bank’s inflation performance against either stated goals – in the case of inflation targeting – or against an implicit goal (a five-year moving average of inflationary outcomes) – where banks have no pre-stated goal. Second, we fashion a measure of monetary policy uncertainty, measuring divergence of inflation and output outcomes versus forecasts. Finally, we measure how out of step a country’s inflation performance is with the world.

Using generalized method of moments (GMM), model selection techniques, and a local projection estimation from a VAR, we find that each percent decline in a central bank’s credibility corresponds with an average 3.6% drop in a country’s institutional resilience since the 1990s. Plainly put, the more that a central bank loses confidence via missing inflation targets or veering from global trends, the more harm it does to overall institutional resilience in a particular country.

The ramifications from this research once again highlight that central bank autonomy may lead to better inflation outcomes, but a central bank can still pursue poor policies or be ineffective even when independence is controlled for. A better performing central bank, that is, one that primarily focuses on price stability, is better for an economy; more importantly, with central banks playing such an important institutional role in an economy, a country’s overall institutional quality may also be dependent on how well a central bank performs. While our results rest on imperfect indicators we have attempted, within the constraints of data availability, to establish the sensitivity of our results to changes in definition, changes in sample periods, and sources of data. Our main findings remain substantially robust across estimation techniques employed.

This post written by Christopher Hartwell and Pierre Siklos.