Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Jamel Saadaoui (University Paris 8).

The recent literature establishes that climate risk reduces the fiscal space, see Beirne et al. (2021) for example. The rationale is intuitive and easy to understand. Financial markets will price the impact of climate risk in the form of higher bond yields and lower ratings on long-term foreign currency debt. This climate risk premium will have important negative implications for the financing of the green transition, especially for emerging markets. However, the literature has not explored the role of financial development and political stability on the climate risk premium. Intuitively, it seems reasonable to think that countries with better financial systems and a more stable political environment will experience smaller pressures on their fiscal space. In a recent paper with John Beirne, Donghyun Park, Jamel Saadaoui, and Gazi Salah Uddin, we investigate this issue. For a sample of 199 economies in 1990-2022, we first empirically confirm that climate risks adversely affect fiscal space. We find that such effects are most pronounced for economies most vulnerable to climate change. However, our evidence indicates that political stability and financial development can mitigate such effects. We also identify nonlinearities in the climate risk-fiscal space nexus. More specifically, the impact of climate risk on fiscal space is greater when fiscal space is most constrained, i.e., at the upper quantile of the distribution.

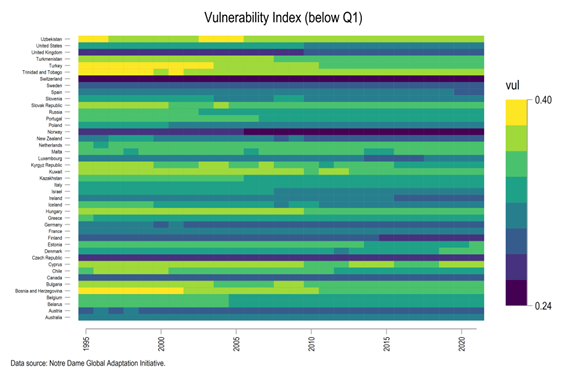

Figure 1. Heat plot for the low vulnerability score.

To measure climate risk, we use the ND-GAIN Vulnerability scores. These scores are forward-looking synthetic measures of vulnerability to climate change. In the Figures 1 and 2, we can see that countries located in sub-Saharan Africa and in South Asia are the most vulnerable to climate risks. Along with the presence of more advanced countries in Figure 1, we find several countries that do not belong to the group of the more advanced economies in terms of economic development. These countries have low vulnerability score (i.e., a higher resilience to climate risks) due to excellent scores in some sub-categories of the ND-GAIN overall vulnerability score, like the infrastructure quality or the energy autonomy sub-categories.

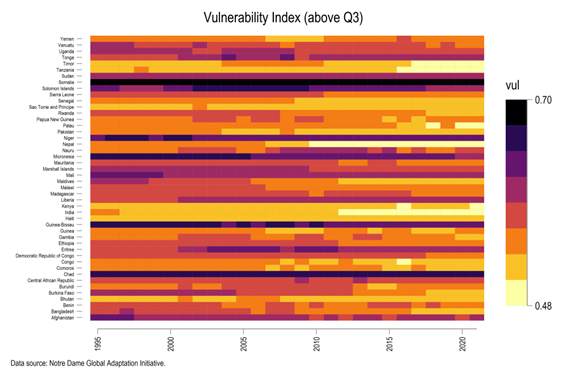

Figure 2. Heat plot for the high vulnerability score.

In Figure 2, we can observe that countries that have a higher vulnerability (above the third quartile). These are countries which tend to be at the lower stages of economic and institutional development. These countries also tend to have less developed domestic financial markets. Relatively to the group of countries presented in Figure 1, this group of countries is more homogenous. We find countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In these countries, the paved road coverage, the electricity access and the access to reliable drinking water remain scare. For example, Chad and Afghanistan have very high vulnerability scores in both the agricultural capacity and the medical staff coverage.

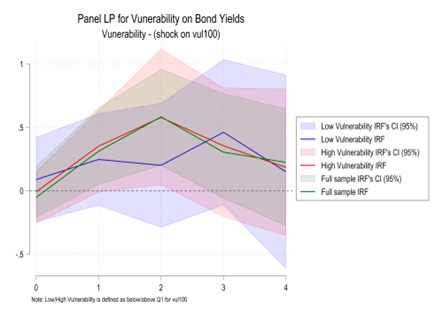

In Figure 3, we use Panel Local projections and a list of domestic and global controls in line with the literature. Our baseline case across all countries indicates a statistically significant premium on sovereign bond yields due to climate risk vulnerability, reflecting the surplus return demanded by investors for holding that debt. Further, we split the sample between low and high climate risk vulnerability, depending on the value of the vulnerability score. For the less climate-vulnerable countries, a statistically significant effect is not found. This is in line with economic intuition, i.e., low levels of climate exposure will not lead to climate-related premia on sovereign bonds. For countries that are highly exposed to climate change, the impact on bond yields is significant, as expected. Interestingly, the effect is broadly in line with that for the panel as a whole in terms of magnitude, suggesting that the countries that are highly vulnerable to climate change may be driving the overall results.

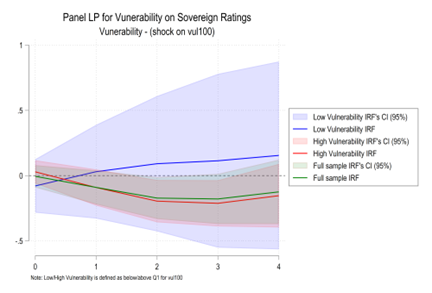

In Figure 4, we perform the same baseline analysis for sovereign ratings, our second measure of the fiscal space. We find a consistent result to that carried out on bond yields, whereby a climate vulnerability shock will lead to a persistent decrease in the sovereign ratings for the full sample and the highly climate-vulnerable countries. For the less vulnerable countries, we do not observe such a persistent deterioration in sovereign ratings, as expected.

Figure 3. Panel LP for the impact of vulnerability on bond yields.

Figure 4. Panel LP for the impact of vulnerability on sovereign ratings.

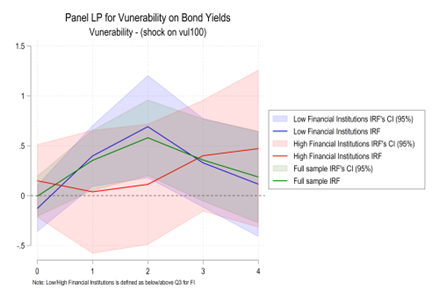

In Figure 5, we use the Financial Institution Development index (Svirydzenka, 2016) to investigate the influence of financial institution development on the impact of vulnerability shocks on the fiscal space. For countries with mature financial institutions, climate vulnerability shocks do not trigger any increase in the bond yields.

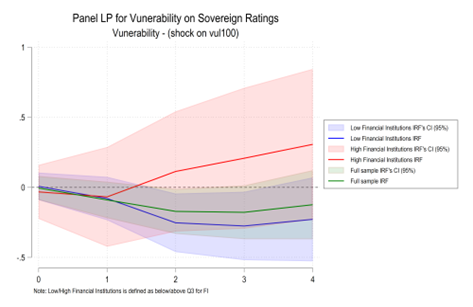

In Figure 6, we can see that climate vulnerability shocks do not have any significant impact on sovereign ratings for countries with elevated levels of financial institution development. On the other hand, climate vulnerability shocks provoke a persistent deterioration in sovereign ratings for the countries with low financial institutions and for the full sample, underlying the importance of sound financial institutions. The mitigating impact of enhanced financial development on the climate-fiscal nexus follows intuition, whereby there is greater depth and liquidity in local financial markets and insurance markets are better developed.

Figure 5. Panel LP for the impact of vulnerability on bond yields (Financial Institutions)

Figure 6. Panel LP for the impact of vulnerability on sovereign ratings (Financial Institutions)

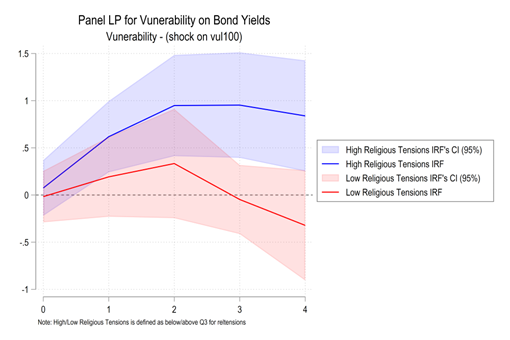

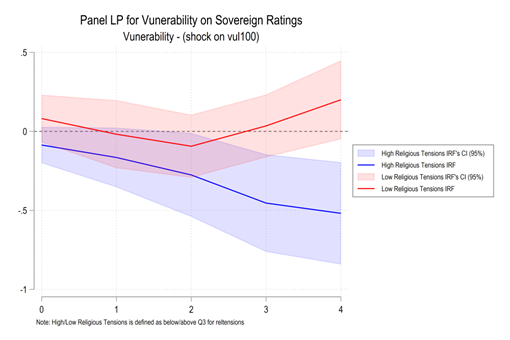

Our result, using ICRG data (PRS group), confirm our main intuition for several dimensions of political stability (External conflict, Internal conflict, Government stability, Ethnic tensions). Countries with more stable political systems experienced a smaller climate risk premium. Remarkably, the climate risk premium is permanent only for one dimension of political stability, which is the religious tensions. These results may help the policymakers to understand the role of political stability and financial development in the funding of the ecological transition.

Figure 7. Panel LP for the impact of vulnerability on bond yields (Religious Tensions)

Figure 8. Panel LP for the impact of vulnerability on sovereign rates (Religious Tensions)

This post written by Jamel Saadaoui.